A great deal of our research is carried out without involving animals. In certain areas, however, animal research remains essential if we are to understand, prevent and cure cancer.

Cancer Research UK only supports research involving animals when there is no alternative.

Thanks to the work of Cancer Research UK and other organisations, cancer survival has doubled over the past 40 years. This achievement would not have been possible without animal research, which has furthered our understanding of the disease, and helped us to discover, develop and test life-saving treatments.

Cancer patients and their families are at the heart of everything we do. Cancer will affect 1 in 2 people during their lives and our ambition is to accelerate progress so that by 2034, more than 3 in 4 people diagnosed will survive. We believe that all our research is vital if we are to achieve this goal and save more lives.

Research involving animals is essential for us to save lives. Most cancer treatments used today wouldn’t exist without this type of work.

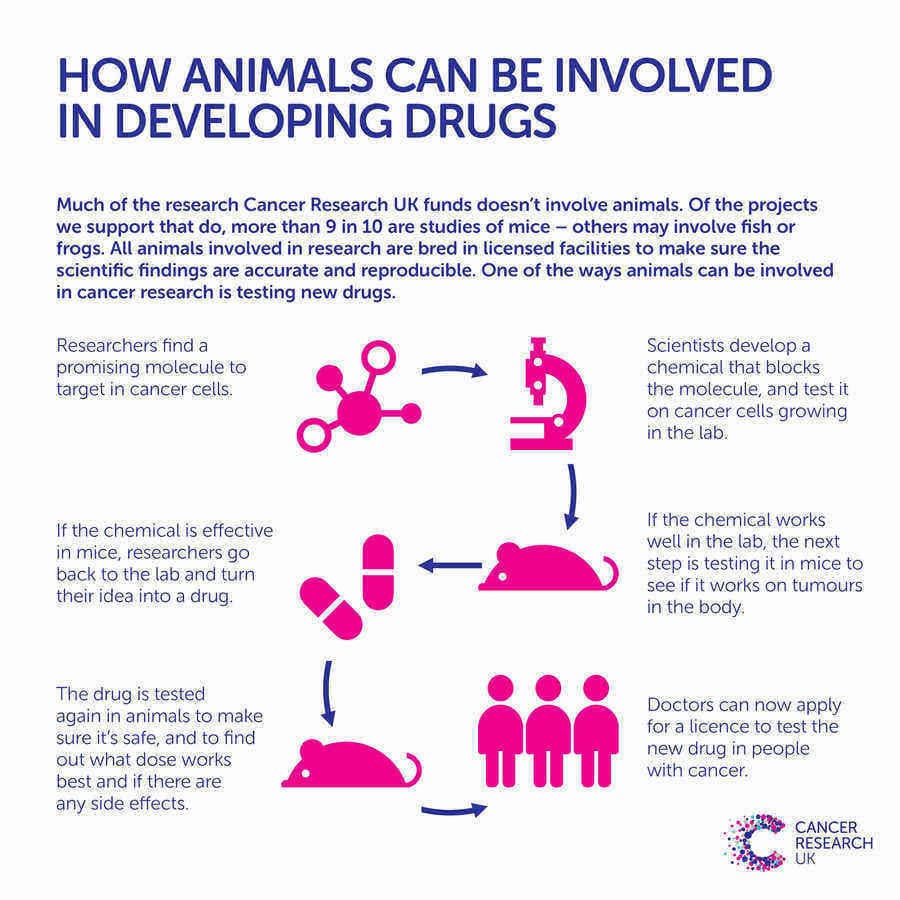

Most of our research doesn't involve animals, but sometimes scientists need to study the biology of cancer in a whole body, rather than individual cells or tissues. Researchers study cancer in animals because they are good models for how cancer behaves in people, helping us understand the disease so we can find better ways to detect and treat it. This includes discovering the faulty genes that cause cancer, investigating how the disease grows and spreads, and exploring how our bodies can help fight tumours.

We also need animal research to improve treatments. It’s an important way to develop and test new drugs, radiotherapy and surgical techniques.

It’s the law in the UK that all new drugs are assessed for safety before they can be tested in people and this usually requires testing in animals. This minimises the risk to cancer patients during the development of new treatments.

Science involving animals has been vital for the discovery of drugs such as tamoxifen for breast cancer, which has saved thousands of women’s lives. And scientists first spotted the potential of Glivec in research involving mice – a drug that cures people with chronic myeloid leukaemia.

Antibody treatments were also developed thanks to animal studies, leading to treatments like cetuximab for bowel cancer, and drugs that harness the body’s immune system to fight cancer.

Animal research has also been crucial for improving radiotherapy and surgery (for example keyhole surgery was first tested in animals), and for developing ways to prevent cancer, such as the HPV vaccine to lower the risk of cervical cancer.

Understanding how faulty genes cause cancer couldn’t be done without animal research because researchers need to look at the whole body, rather than individual cells or tissues. By making genetically engineered mice – something that can’t legally be done in people – scientists helped prove that faulty versions of genes like BRCA1 and APC are behind many cancers. And this knowledge has led to ways for people who inherit these faulty genes to reduce their cancer risk.

It’s important we take every step to protect animals’ welfare.

Research involving animals is not undertaken lightly; it’s governed by strict laws in the UK. These laws ensure that research involving animals is only used when there is no alternative. Researchers are also legally required to involve the smallest number of animals and take every step possible to minimise distress.

All animals involved in our research are under the supervision of vets and trained animal technicians who are responsible for the animals’ welfare. The research must be carried out by licensed people at licensed premises, which are regularly checked without notice by government inspectors.

And all animal research has to be approved by an ethics panel that includes members of the public. They must agree that the work is necessary, that the animals are being cared for correctly and that the potential benefits are worthwhile.

There are strict guidelines about the conditions that animals are kept in to make sure their environment meets their needs. For example, the temperature, lighting and noise levels are all controlled to keep the animals comfortable. Animals must have correctly sized housing to avoid over-crowding, and have access to ample food and water, and bedding and toys if appropriate.

Animals are also checked daily for any health problems.

All our researchers follow the 3Rs – principles that are well established to improve research involving animals.

Replacement – looking for approaches that don't involve animals

Reduction – reducing the number of animals involved

Refinement – introducing ways to reduce any pain or stress experienced by animals

Our researchers are helping to improve animal research using these principles. This includes doing experiments on cells grown in the lab, examining samples of human tumours and using sophisticated computer programmes to understand how cancer behaves.

Scientists are also developing cutting edge ways to grow miniature 3D tumours in the lab. This will help to uncover how tumour cells communicate with the healthy cells around them and test new drugs in a more realistic way without involving animals.

Researchers are designing tests that could predict side effects of new cancer treatments that boost our immune system. Using small samples of human blood might mean fewer animals are needed to check a drug’s safety.

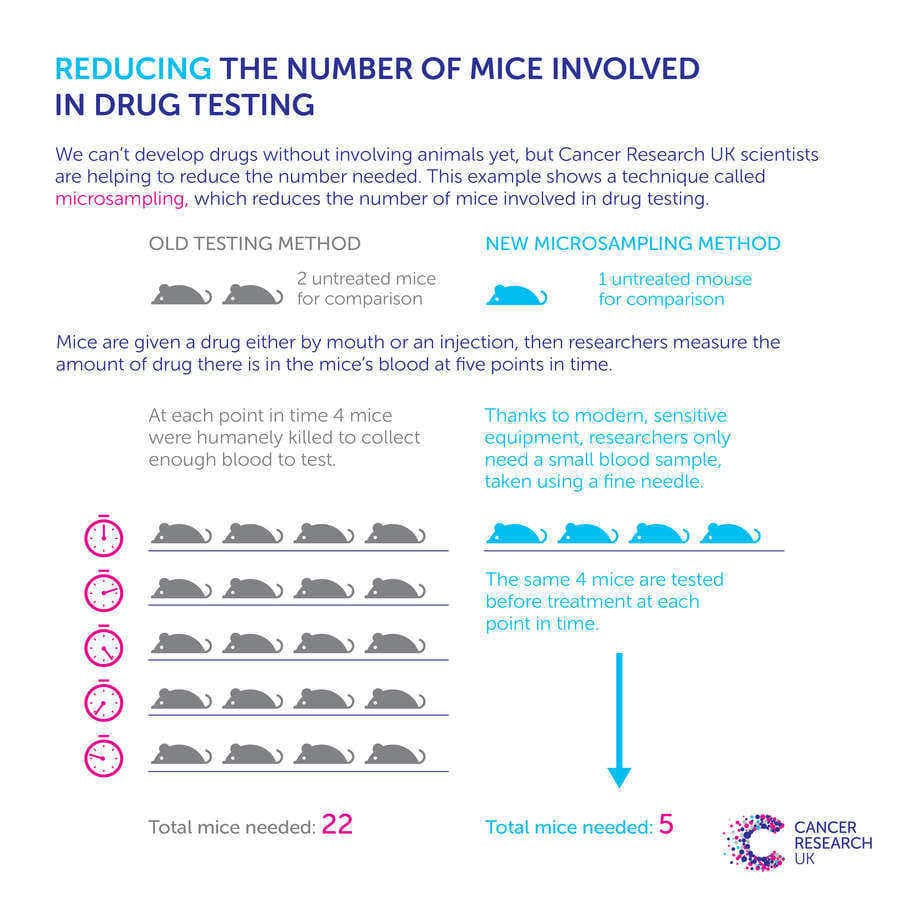

We've funded research into a technique that reduces the number of mice needed for drug testing by using more sensitive equipment to measure levels of a drug in the mice's bloodstream. The diagram below explains more.

Completely replacing all animals in research is not yet possible. For now we will continue funding the highest quality research – including research involving animals – to help beat cancer sooner.

We’re committed to supporting the principles of the 3Rs in our research. Below are some examples of how our scientists are replacing, refining and reducing animals in cancer research.

Our PEACE study is shedding light on what happens during the final stages of cancer. Traditionally this type of research has been carried out in animals, but this nationwide project is collecting samples from people who have died from cancer in a bid to understand how tumours spread and stop responding to treatments. In turn, this innovative approach could reveal new ways to tackle the disease.

We’re supporting and are an active member of the international Human Cancer Models Initiative, a collaboration that’s creating miniaturized versions of tumours in a dish – ‘organoids’. Reflecting a range of cancers, these organoids will help scientists across the world to replace animals in some of their research, such as studies into potential new treatments, and will complement research where animals are necessary.

Our Centre for Drug Development (CDD) is working on ways to replace animals in drug safety studies, for example by pooling existing data to show how a potential new treatment is likely to work in people

Professor Kevin Brindle from our Cambridge Institute(link is external) is researching better ways to image cancer. He’s developing highly sensitive techniques that can scan tumours in the same living animal – and in patients – over time. This means far fewer animals need to be used in each experiment.

At our Cambridge Institute, a team led by Professor Carlos Caldas is developing new ways to accurately mimic human breast cancers in the lab. They’ve taken breast cancer samples from patients and grown them in mice. They have also pioneered a technique to grow cells in dishes from these tumours in mice to allow testing hundreds of cancer drugs for each patient’s cancer. This could help researchers better predict how individual patients might respond to treatments in clinical trials, while reducing the number of animals needed in pre-clinical studies.

Our Centre for Drug Development (CDD) brings much needed new treatments to people with cancer. Here, our scientists are continually working to improve drug safety research and use new techniques that reduce the number of animals involved, without affecting the reliability of these studies.

Scientists from our Manchester Institute’s Biological Resources Unit recently introduced swings for mice housed at the facility, to enhance their environment and improve animal welfare. These award-winning swings are now being made into a commercial product and have been praised for their potential to make a great impact on animal welfare.

At our Manchester Institute, Professor Caroline Dive’s team is developing blood tests – ‘liquid biopsies’ – to track and monitor lung cancer. Mice have been crucial to this research, but the group has been working on ways to refine their techniques. For example they no longer use a surgical operation to study patient tumours in the animals, and they’ve reduced the number of mice needed to test out new drugs.

Cancer Research UK is a member of the Association of Medical Research Charities (AMRC) and endorses the AMRC's position on the use of animals in medical research. All AMRC member charities support this principle, as outlined in this statement.

We are a signatory to the Concordat on Openess on Animal Research which sets out how organisations report the use of animals in scientific, medical and veterinary research in the UK.

We have also made a committment(PDF, 399 KB) with funders across Europe towards ensuring responsible research involving animals.

For further information about involving animals in our research:

Here are some links to information from other organisations: