A trial comparing olaparib with chemotherapy for breast cancer with a change to the BRCA 1 or BRCA 2 gene (OlympiAD)

Cancer type:

Status:

Phase:

This trial compared olaparib with chemotherapy for breast cancer that has spread. It was for people who have breast cancer and a change to the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.

The trial was open for people to join between 2014 and 2015. The research team reported these results in 2020.

More about this trial

Breast cancer that has spread to another part of the body is called metastatic or secondary breast cancer. Doctors often treat secondary breast cancer with chemotherapy. Researchers wanted to see if a drug called olaparib was useful for people in this situation.

Olaparib is a type of targeted cancer treatment called a PARP inhibitor. It blocks an enzyme called PARP that cancer cells need to repair themselves. Research had shown that PARP inhibitors work better for people who have a change (mutation) in genes called BRCA1 or BRCA2.

In this trial, some people had chemotherapy and some people had olaparib.

The main aim of the trial was to find out which treatment is better for people who have breast cancer that has spread and have a change in a BRCA gene.

Summary of results

The research team found that olaparib may be a useful treatment for breast cancer that has spread.

Trial design

This trial was for people who had breast cancer that had spread, and a change in either the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.

The people taking part were put into a treatment group at random. Some had olaparib, and some had chemotherapy. For those who had chemotherapy, their doctor decided which chemotherapy drug was best for them.

Results

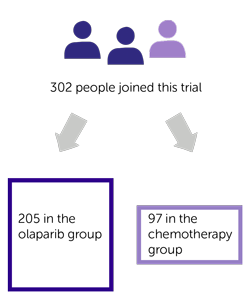

A total of 302 people joined this trial. They were put into 1 of 2 treatment groups at random. There were:

- 205 people in the olaparib group

- 97 people in the chemotherapy group

Six people in the chemotherapy group decided not to go ahead with treatment as part of this trial. So 91 people in the chemotherapy group had treatment:

- 41 had capecitabine

- 16 had vinorelbine

- 34 had eribulin

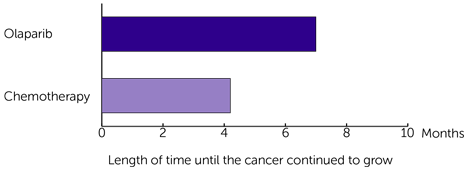

The research team looked at how long it was before the cancer continued to grow. They found it was longer for those who had olaparib:

- 7.0 months for those who had olaparib

- 4.2 months for those who had chemotherapy

The difference between the two groups is big enough for the team to conclude it was because of the treatment. And not due to chance.

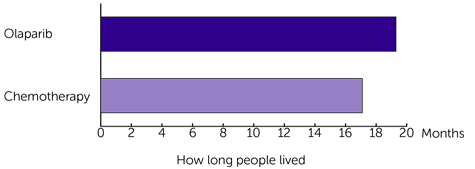

When they looked at how long people lived, they found there was less of a difference between the 2 groups:

- 19.3 months for those who had olaparib

- 17.1 months for those who had chemotherapy

The results for the 2 groups look quite different. But the difference between how long people lived isn’t big enough to say for sure that it was because of the different treatments. It could have been due to chance.

Quality of life

The research team asked people taking part to fill out a quality of life questionnaire before, during and after treatment.

The results showed that there wasn’t much change in quality of life for people in either group. It went up slightly for those who had olaparib. And down slightly for those who had chemotherapy.

Side effects

Most people who took part in this trial had at least 1 side effect. Most were mild or didn’t last long. But some people had side effects that were more severe.

The most common of those side effects was a drop in red blood cells for people who had olaparib. And a drop in red and white blood cells for those who had chemotherapy.

Conclusion

The research team concluded that olaparib helped increase the time before the cancer started to grow. This was for people who have breast cancer that has spread and a change in the BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene.

They also found it didn’t cause too many side effects, or any unexpected side effects.

They suggest more trials are done to find out which groups of patients olaparib will work best for. For example, people who have had specific treatments before, or those who have certain hormone receptors.

Where this information comes from

We have based this summary on information from the research team. The information they sent us has been reviewed by independent specialists ( ) but may not have been published in a medical journal. The figures we quote above were provided by the research team. We have not analysed the data ourselves.

) but may not have been published in a medical journal. The figures we quote above were provided by the research team. We have not analysed the data ourselves.

Recruitment start:

Recruitment end:

How to join a clinical trial

Please note: In order to join a trial you will need to discuss it with your doctor, unless otherwise specified.

Chief Investigator

Dr Anne Armstrong

Supported by

AstraZeneca

NIHR Clinical Research Network: Cancer

If you have questions about the trial please contact our cancer information nurses

Freephone 0808 800 4040