Randomised trials

This page tells you about randomised clinical trials. It has information about

What randomisation is

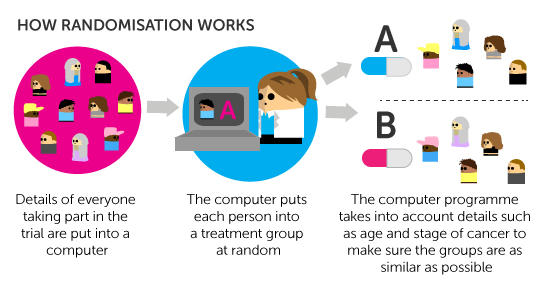

Most phase 3 trials, and some phase 2 trials, are randomised. This means that there are at least 2 different groups in the trial and people taking part are put into one or other group at random. This 'randomisation' is usually done by a computer. Certain details about you (such as your age, gender or the stage of your cancer) are put into the computer first. This is to make sure the different groups in a trial are as similar as possible.

Each group in the trial has a different treatment. If there are 2 groups, one group has the new treatment being tested and the other has the standard cancer treatment they would have if they were not in the trial. People having the standard treatment are called the control group. A randomised trial that has a control group is called a randomised controlled trial.

There may be more than 2 groups. Some trials test more than one new treatment or combination of treatments. Others may test variations in one particular new treatment – for example different doses of the same drug. There will still be a control group, which has the standard treatment.

Sometimes people in the control group take a dummy treatment, called a placebo. Doctors only set up trials this way if there is no standard treatment available for the control group to have.

Why trials are randomised

Researchers randomise trials because they need to be sure that the results are correct and there is no bias that could distort the results.

Of course, researchers are unlikely to be deliberately biased. But it is possible to be biased without realising it. For example, if a new treatment has quite bad side effects the doctors running the trial might subconsciously avoid putting patients who are more ill into the group having the new treatment. So as the trial went on, the control group would have more and more of the ill patients in it. The people in the new treatment group would then do better than the control group. So, when the trial results come out, the new treatment would look as if it works better than the standard treatment. But really it doesn't.

Details of all the people in the trial are put into the computer to help with randomisation. The details include age, gender and stage of the cancer. This makes sure that the groups are reasonably equal. For example, if doctors didn't take cancer stage into account for some trials, they could end up with one group containing people with more advanced cancers and this could also bias the trial results.

The placebo effect

Patients can also be biased. Many of us feel better if we believe we have taken something to make us feel better. Even if we've only taken a tablet made of chalk or sugar. This is called the placebo effect.

Phase 3 trials could compare a new treatment with no treatment at all. But then, the people getting the new treatment might feel better, even if the new treatment didn't work. They would have the placebo effect. The people getting no treatment wouldn't feel any better, of course. So, some trials compare a new treatment with a dummy treatment called a placebo. The dummy treatment looks exactly like the new treatment – for example, the same shape or colour of pill, or size of injection. The two groups of patients then can't be biased, because they won't know if they are getting the placebo or the new treatment.

A placebo is only used if there is no standard treatment available. The patients in the control group wouldn't have any treatment if they weren't in the trial. So they are not missing out on treatment they would otherwise have had. It isn't ethical to give a placebo to a group of people who really need a treatment for cancer. So the research ethics committee would not give permission for a trial designed in that way.

Blind trials

A blind trial is a trial where the people taking part don't know which treatment they are getting. They could be getting the new treatment. Or they could be getting standard treatment or a placebo, depending on the design of the trial. All patients receive identical injections or tablets, so they can't tell which treatment they are having.

Double blind trials

A double blind trial is a trial where neither the researchers nor the patients know what they are getting. The computer gives each patient a code number. And the code numbers are then allocated to the treatment groups. Your treatment arrives with your code number on it. Neither you nor your doctor knows whether it is the new treatment or not.

The list of patients and their code numbers is kept secret until the end of the trial. In an emergency the researchers could find out which trial group a patient was in, but generally no one knows until the trial had finished.

Related Information

Questions about clinical trials?

Speak to a nurse

Randomised trials

Randomised trials