Radiotherapy for bile duct cancer

Radiotherapy uses high energy x-rays to treat cancer cells. For bile duct cancer, you usually have external radiotherapy. This means using a radiotherapy machine to aim radiation beams at the cancer.

You have this treatment in the hospital radiotherapy department. It doesn't hurt, although laying on the radiotherapy couch can be uncomfortable.

When you might have radiotherapy for bile duct cancer

Radiotherapy isn't a common treatment for bile duct cancer. You might have it if you can't have surgery. Or to help control symptoms caused by bile duct cancer spread. This is called palliative treatment.

Radiotherapy to help control symptoms

Your doctor might suggest that you have radiotherapy to help control symptoms such as pain. Radiotherapy can help to shrink the cancer and make you feel better.

You might have 1 treatment or a few treatments given over a few days. These treatments are sometimes known as fractions.

Types of radiotherapy for bile duct cancer

You usually have external radiotherapy. This means that a radiotherapy machine aims the radiation beams at the cancer.

There are different types of external radiotherapy. Your doctor decides which is best for you.

You are most likely to have conformal radiotherapy or intensity modulated radiotherapy (IMRT). These shape the radiation beams to closely fit the area of the cancer.

Stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT)

Researchers are looking into a type of radiotherapy called stereotactic body radiation therapy (SBRT). This gives radiotherapy from many different positions around the body. The cancer receives high doses of radiation but the surrounding tissues only get a low dose. This lowers the risk of side effects.

Your doctor might ask you to enter a clinical trial looking at SBRT for bile duct cancer.

Selective Internal Radiation Therapy (SIRT)

Selective internal radiation therapy is a type of internal radiotherapy. It is sometimes called radioembolisation or trans arterial radioembolisation (TARE).

SIRT is a way of giving radiotherapy treatment to the liver. Your doctor puts tiny radioactive beads into a blood vessel that takes blood into your liver. The beads get stuck in the small blood vessels in and around the cancer, and the radiation destroys the cancer cells.

SIRT isn't routinely used for people with bile duct cancer in the UK. Your doctor may be able to make a special application if they think this can help you or ask you to join a clinical trial.

Planning your radiotherapy treatment

You have a planning session with your radiotherapy team a few days before you start treatment. This means working out the dose of radiotherapy you need and exactly where you need it.

Your planning appointment takes from 15 minutes to 2 hours.

You usually have a planning CT scan in the radiotherapy department.

The scan shows the cancer and the area around it. You might have other types of scans or x-rays to help your treatment team plan your radiotherapy. The plan they create is just for you.

Your radiographers tell you what is going to happen. They help you into position on the scan couch. You might have a type of firm cushion called a vacbag to help you keep still.

The CT scanner couch is the same type of bed that you lie on for your treatment sessions. You need to lie very still. Tell your radiographers if you aren't comfortable.

Injection of dye

You might need an injection of contrast into a vein in your hand. This is a dye that helps body tissues show up more clearly on the scan.

Before you have the contrast, your radiographer asks you about any medical conditions or allergies. Some people are allergic to the contrast.

Having the scan

Once you are in position your radiographers put some markers on your skin. They move the couch up and through the scanner. They then leave the room and the scan starts.

The scan takes about 5 minutes. You won't feel anything. Your radiographers can see and hear you from the CT control area where they operate the scanner.

Ink and tattoo marks

The radiographers make pin point sized tattoo marks on your skin. They use these marks to line you up into the same position every day. The tattoos make sure they treat exactly the same area for all of your treatments. They may also draw marks around the tattoos with a permanent ink pen, so that they are clear to see when the lights are low.

The radiotherapy staff tell you how to look after the markings. The pen marks might start to rub off in time, but the tattoos won’t. Tell your radiographer if that happens. Don't try to redraw them yourself.

After your planning session

You might have to wait a few days before you start treatment. During this time the physicists and your radiographer doctor (clinical oncologist) decide the final details of your radiotherapy plan. They make sure that the area of the cancer will receive a high dose and nearby areas receive a low dose. This reduces the side effects you might get during and after treatment.

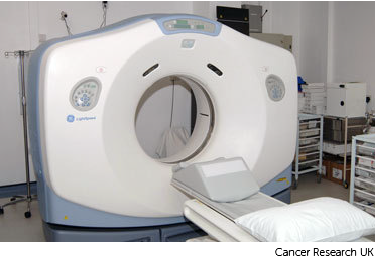

The radiotherapy room

Radiotherapy machines are very big and could make you feel nervous when you see them for the first time. The machine might be fixed in one position. Or it might rotate around your body to give treatment from different directions. The machine doesn't touch you at any point.

Before your first treatment, your  will explain what you will see and hear. In some departments, the treatment rooms have docks for you to plug in music players. So, you can listen to your own music while you have treatment.

will explain what you will see and hear. In some departments, the treatment rooms have docks for you to plug in music players. So, you can listen to your own music while you have treatment.

Before each treatment session

The radiographers help you to get onto the treatment couch. You might need to raise your arms over your head.

The radiographers line up the radiotherapy machine using the marks on your body. Once you are in the right position, they leave the room.

During the treatment

You need to lie very still. Your radiographers might take images (x-rays or scans) before your treatment to make sure that you're in the right position. The machine makes whirring and beeping sounds. You won’t feel anything when you have the treatment.

Your radiographers can see and hear you on a CCTV screen in the next room. They can talk to you over an intercom and might ask you to hold your breath or take shallow breaths at times. You can also talk to them through the intercom or raise your hand if you need to stop or if you're uncomfortable.

The short video below shows how you have radiotherapy:

Dan (radiographer): Before your treatment starts your doctor will need to work out exactly where the treatment needs to go and also which parts need to be avoided by the treatment. To have radiotherapy you lie in the same position as you did for your planning scans. We then line up the machine based on your tattoo marks. It is really important that you stay very, very still when you are having treatment it is also important to let the radiographers know right at the beginning if you are not comfortable so they can adjust your position.

Radiographer: Ok all done, we’ll be back in a couple of minutes.

Dan (radiographer): We leave the room and control the room from a separate room This is so we aren’t exposed to radiation. Treatment takes a few minutes and you will be able to talk to us using an intercom. We can see and hear you while you are having your treatment and will check that you are ok. When your treatment starts you won’t feel anything; you may hear the machine as it moves around you giving the treatment from different angles. Because we are aiming to give the same treatment to the same part of the body everyday then the treatment process is exactly the same everyday so you shouldn’t notice any difference. You’ll see someone from the team caring for you once a week while you are having treatment they’ll ask how you are and about any side effects.

Patient: They get you from one sitting area to another and then take you into the room where you undress to the waist and then lie down and line you up by either moving you or asking you to shuffle a little and they check the dimensions and they talk to one another and they say I am fine this side how are you ...yes fine...ok, stay where you are Jeff and that was it. There were a few little clicks and lights go on and off and you can see a green laser beam which lines up with certain things on your body uh so no, no real noise and no discomfort.

You won't be radioactive

External radiotherapy won't make you radioactive. It's safe to be around other people, including pregnant women and children.

Side effects of radiotherapy

For bile duct cancer, you usually have a short course of radiotherapy treatment of only a few days, so you might have very few side effects. You are likely to have more side effects if you have treatment for a couple of weeks.

Side effects tend to start a week after the radiotherapy begins. They gradually get worse during the treatment and for a couple of weeks after the treatment ends. But they usually begin to improve after around 2 weeks or so.

Tiredness and weakness

You might feel tired during your treatment. It tends to get worse as the treatment goes on.

Various things can help you to reduce tiredness and cope with it, such as exercise. Some research has shown that taking gentle exercise can give you more energy. It's important to balance exercise with resting.

Feeling or being sick

You might feel sick at times. Let your treatment team know if you feel sick, as they can give you anti sickness medicines.

Reddening or darkening of your skin

Your skin might go red or darker in the treatment area. You might also get slight redness or darkening on the other side of your body. This is where the radiotherapy beams leave the body.

Diarrhoea

Radiotherapy to the tummy (abdomen) can cause diarrhoea. Drink plenty of fluids and let your doctor know if you have frequent diarrhoea.

Radiotherapy can cause many different side effects, such as tiredness. The side effects you get will depend on the area you're having treatment to, but there are some general side effects you might experience regardless of where your cancer is. This video is about the general side effects you might have.

On screen text: Tiredness and weakness

Martin (Radiographer): As the normal cells repair themselves from the treatment this can use a lot of the body's resources, causing tiredness.

David: After about four weeks, I started to get tired. The body was starting to weaken.

Laurel: I was tired, day and night. Getting up in the morning was like a chore. I couldn't talk for 5 minutes. I would just sleep and just sleep and just wake up and sleep again.

Martin (Radiographer): Listen to your body. Take rests if you need to. Try not to overdo things.

Laurel: Don't fight with yourself too much. Just like go at a pace and just work with your body. If you can't make it today, you can't make it today.

David: You've got to rest. You have to take the time to rest.

Mary: Just going for them small walks. They really do help you. And even if it is just walking around your house or just walking around the block.

Martin (Radiographer): Doing exercise can help with tiredness by helping you maintain energy levels.

Mary: Being outside, that's a big, massive thing as well because you're feeling the fatigue and I think getting outside, just getting a bit of fresh air that really, really did help me.

Martin (Radiographer): The tiredness you can expect to begin within the first few weeks of treatment. Once it reaches its peak, about two weeks after treatment it recovers quite quickly after that.

Mary: It's not forever. You're not going to be like this forever and I did have to tell myself that.

Laurel: Two months after treatment, I start to feel less tired and that was a way forward because things start to really improve.

On screen text:

- Rest and have short naps when you need to

- Drink plenty of water

- Eat a balanced diet

- Do some gentle exercise

- Get some fresh air

On screen text: Sore skin

Martin (Radiographer): The radiotherapy can cause soreness of the skin. This only affects the area that you are having treated. This usually starts to appear about two weeks after you start treatment. You may notice this becoming more red and may become more itchy and sore as treatment continues.

David: After about ten days I started to get red on the area that they were targeting and it just progressively got redder and redder.

Laurel: My skin was dry and at the back was just like this triangle shape thing where it was like, okay, I'm a woman of colour, but it was really, really black.

David: Wasn't too painful, it was sort of annoying, rather than painful.

Martin (Radiographer): After treatment’s finished, the skin will remain sore for up to two weeks, but then recovers quite quickly.

Laurel: I haven’t got no scarring now at all.

David: It was maybe three or four weeks and then all the blemishes disappeared front and back.

Martin (Radiographer): When you start treatment we would advise you to carry on with your normal skincare routine but as the side effects develop, then your team will advise you on which products you can use on the skin safely.

Laurel: When I'm washing myself I use a sponge and you're just literally as it were just squirt it down, you don't rub the skin at all because it's already damaged. Pat dry, don't rub.

David: I spoke to the hospital about it and it was them that recommended this cream to put on, just to alleviate the symptoms.

Martin (Radiographer): We'd recommend wearing loose clothing and keeping the treatment area covered up against the sun and wind.

Laurel: I had to change most of my wardrobe. I only wore cotton.

David: Wearing T-shirts, soft clothing, nothing that would rub.

Mary: It's important when you go outside to make sure that you do wear that headscarf, or you do wear a hat or whatever it is.

Laurel: I wouldn't go in the sun at all, at all because my skin was - I know it was too delicate.

On screen text:

- Don’t rub the area, press if it is itchy and dab your skin dry

- Don’t use perfume, perfumed soaps or lotions on the area

- Don’t shave the area

- Only use creams or dressings advised by your specialist or radiographer

- Wear loose fitting clothing

- Avoid strong sun or cold winds

- Make sure you wear sunscreen

On screen text: Hair loss

Martin (Radiographer): Radiotherapy can cause hair loss in the area that's being treated, whereas chemotherapy can cause hair loss all over the body.

Mary: 2 to 3 weeks after the radiotherapy, I was brushing my hair and loads came out on the brush. I knew it was going to happen, but it was just hard when it happened.

Martin (Radiographer): In most cases the hair will grow back. This can take a couple of months and the hair may have a slightly different colour or texture.

Mary: Mine did grow back and there's a lot of grey in it so I have to dye it. This is not my original colour. It's very slow growing back.

Martin (Radiographer): Use a simple soap to clean the area. Be gentle with the skin in that area and after washing pat the area dry with a soft towel.

On screen text:

- Radiotherapy can make hair fall out in the treatment area

- It won’t cause hair to fall out in other parts of your body

- Your hair might grow back a few weeks after treatment ends

- If your hair won’t grow back, then your doctor should tell you

- Don’t use perfume, perfumed soaps, or lotions on the area

On screen text: Your mental health

Laurel: I felt frustrated. Some days were really, really challenging where there were just tears without words.

Mary: It's a mixture of emotions. You feel angry and you feel frustrated. You lose your confidence.

Martin (Radiographer): Radiotherapy can cause a lot of emotions at various times during the treatment. You may feel sad or anxious or depressed, which is quite normal. It's good to talk to people about your experiences, whether that's your team at the hospital or friends and family.

David: I couldn't praise the team highly enough. Everybody that was involved were unbelievable and if it hadn't been for them, I just don't think I would have gotten through with it.

Mary: I did have a nurse as well and she had the experience of dealing with people that went through brain surgery, went through radiotherapy so it was just great that I could reach out.

Martin (Radiographer): Your team will be able to give you information about local patient support services that are available, that includes things like counselling and complementary therapies.

Laurel: A referral from the hospital counselling, which I attended for about a year.

Martin (Radiographer): There's also lots of support available online and in your local area.

Mary: I went on loads of different forums and I spoke to loads of different people and it really, really helped me. If I didn't do that, I don't think I would have got through most days.

Laurel: If you get a bit cranky or feel a bit low, go for it. But there's so much help out there and that's why I'm pushing forward like don't sit down in silence. It's the same thing, just get the help you need.

On screen text:

- There is help available – ask the hospital for support

- Talk to your friends and family about how you are feeling

- Ask about local support groups

- Your GP or hospital can provide counselling

- You can get help and support online through forums

If you're experiencing a side effect that hasn't been covered in this video, you can find more information on the Cancer Research UK website.

On screen text: For more information go to: cruk.org/radiotherapy/side-effects